Do you really know everything about the town you grew up in? Are you aware of all its secrets and rich history?

Archaeology has always fascinated me, especially marine archaeology. While researching artifacts discovered in and around the Albemarle Sound, the Chowan River, and nearby lands, I stumbled upon numerous research papers from the mid-seventies. These papers detailed a colonial site in my hometown of Edenton that I had never heard of in my 30-plus years living there – the Edenton Tannery.

In this post, we will dive deeper into the historical significance of the Edenton Tannery and uncover its hidden stories.

What is a tannery?

A tannery is a place where animal hides are tanned, or treated to be converted into leather. As the act of tanning itself could possibly induce a nefarious odor due to the substances used and, well, the rotting flesh, tanneries were often located on the outskirts of towns, usually near some sort of flowing water source.

Tanneries were incredibly important in Colonial America, as they were used to create strong leather which in turn, was made into harnesses, saddles, shoes, etc. Some completed hides were also sent back to England.

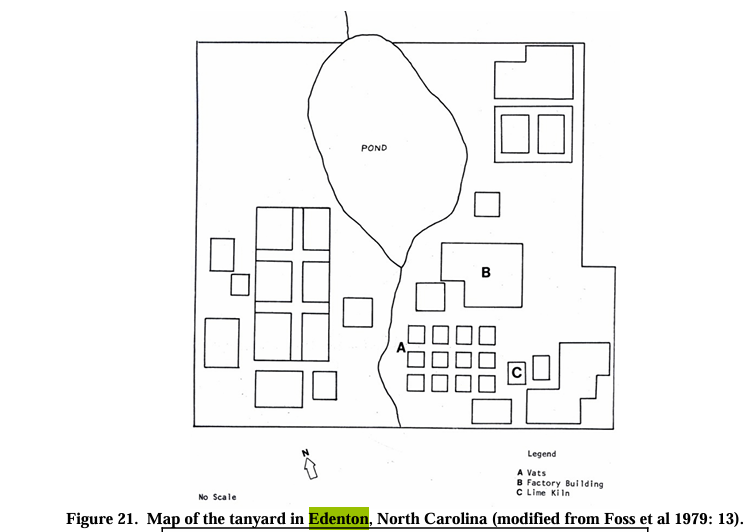

Tan yard layouts were generally pretty similar, the Edenton one included (being very similar to the Shriver Tanyard located in Maryland). The layout included a water source, lime kiln, a grouping of tanning vats, and a drying shed. Most would also contain a bark shed and bark mill, however, these were not indicated during the more formal excavation of the Edenton site (that I’ll share a little more about later).

Where was the Edenton Tannery?

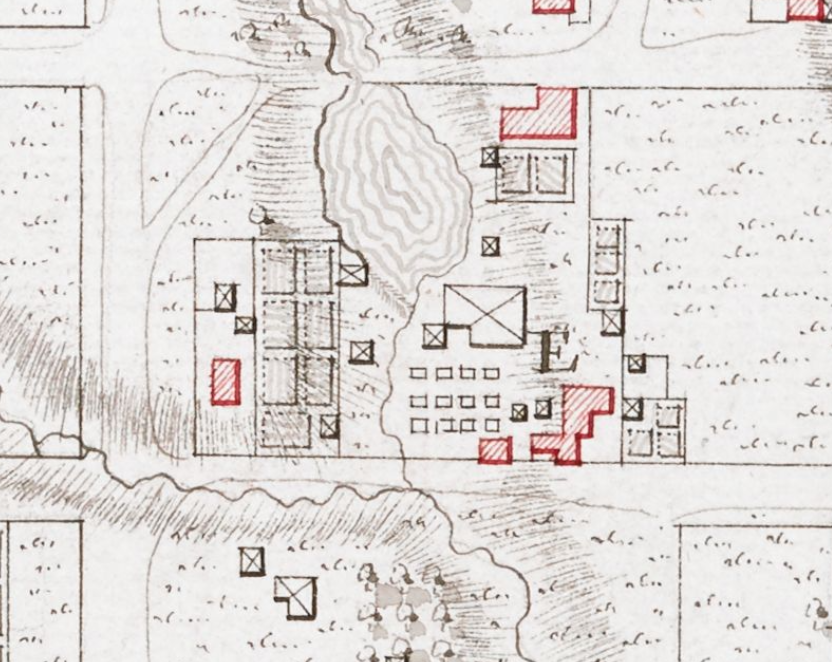

The tannery, which was named the William Jackson and Co. Tanyard (1757), was located on the block where the Chowan County Detention Facility is now located, on the eastern side (it is unknown what was on the western half).

From what I’ve read, it seems to me that the only reason there was an archeological inquest into the particular spot is that the town was fixing to build the facility. Tanning isn’t exactly a glamorous art and overall, it is hard to find a wealth of information on colonial-era tanning.

The remains of the colonial tanyard complex are situated ·in downtown Edenton in the southeast corner of a block bounded on the north by Church Street, on the west by Broad Street, on the south by Queen Street, and on the east by Court Street. The area of the site is approximately one-half acre.

National Register of Historical Places Nomination Form, circa 1973

According to the nomination form for the National Register of Historical Places, which was completed well before my time, the remains of the colonial tanyard complex was the only colonial tanyard in North Carolina (at that point – it may have changed in the subsequent decades) with intact remains verified by archeological testing. Continuing on from that, it was stated that “the Edenton Tannery was in fact the first formally incorporated business in Edenton”.

I will say, in a town that prides itself on its historical preservation, it is a bit disappointing that more of an effort was not made to preserve one of the town’s historical industrial activities. Yes, it does not have the same charm as the “Edenton Tea Party”, but it was still a valuable part of the daily lives of our citizens.

In order to preserve some of the site, the Chowan County detention facility originally proposed for construction in the southeastern corner of the block was eventually built on the northeastern corner to avoid destroying the tannery remains.

In 1977, the tan yard was formally archaeologically tested by SSI, Earth Systems Division, of Marietta, Georgia and testing at the site included regularly spaced shovel testing and pH testing. This survey revealed a tannery operation on the tract that operated from 1757 to 1770 with significant intact cultural features, although many of the features existed below the water table.

According to the survey, “The rationale for that approach [pH testing] was that the tannery should have left fairly massive subsurface remains, and that the use of tanning bark over a period of time would have permanently altered the soil pH in the immediate areas used for tanning activities. The survey method proved to be extremely effective, and evidence of the tannery in the form of well preserved tanning vats and a lime kiln was found.”

The Edenton site also seemed to share space with the Snuff and Tobacco Manufacture (located on the eastern side as well), based on circumstantial evidence uncovered during that survey.

I linked to the full survey at the end of this post, but one of the things that stood out to me most about this survey was that it seemed to be underfunded and the field crew were rushed (due to the lack of funding). While some very interesting things were found, like a cellar and a ton of artifacts, within the areas they excavated, I wonder what else would have been uncovered if the team had been allocated more resources.

The Tanning Process

Tanning, particularly in the colonial era, was a slow process. Everything took time and it wasn’t uncommon for the process to take upwards of two years. Even the ingredients/chemicals used for tanning took time to produce. Remember, this was back in the time before conveniences like Wal-Mart. While there may have been some local shops, there were no guarantees that the sellers would have had any of the materials needed for the tanning process. More than likely, it would have all been produced by the tanner (or really, his apprentice) on-site.

That being said, tanners used what they could source locally, in terms of both the animals that were utilized and the exact ingredients they used. In our area, deer would have been one of the main animals used within the tanning process, but cattle, horses, and sheep were also frequently utilized.

In any community, tanneries were always situated near a source of running water. These sites typically included pits for collecting waste products, which were useful as compost in the spring.

After slaughtering, the hides were washed in the river or stream to remove blood, loose flesh, and other impurities, then soaked in water until ready for further processing. Cattle, swine, sheep, and goats provided most of the hides commonly used.

The most critical part of the tanning process involved vats containing various noxious solutions. These large containers, typically about 12 feet square, were slightly sunken with earthen walls to retain water diverted from a stream or river.

The first vat contained a weak lime solution, obtained more than likely from oyster shells in our area, into which the hides were placed hair side down. The chemical reaction caused some hair to fall off. The hides were then removed, and the bleached fat and hair-lime residue was scraped off (fun fact: the residue would later be sold for plastering).

The hides, now mostly hair-free, were returned to stronger liming vats, that contained large quantities of decaying organic matter full of bacteria that aided in removing hair and connective tissue. This process, involving alternating periods of soaking and drying over about two months, made it easy to remove the remaining hair without damaging the hide.

This process would take about four months to a year.

After completion of the liming process and removal of all hair, the hides were immersed for short periods in vats containing a solution of water, salt, and manure or potash. The purpose of these “bate” vats was to enlarge the pores of the hides so that they would better absorb the tanning liquor. Once removed, they would be washed and “beamed”, which removed any remaining hair, tissue, or fat.

Next, the hides were treated with oak bark (the poplar choice in our area) which provided the tannic acid necessary for preserving and coloring the hide (other additives, such as beech, or willow bark, could have been used as well for various shades). Bark was spread at the bottom of the tanning pit, with hides and bark alternately stacked until the pit was full. A foot of tanbark covered the pit, which was well trampled down and kept moistened for three months.

Unpacking the pit was risky because the hides were very soft and prone to tearing.

The hides would then be dried and conditioned for use.

Tanning is hard work and it certainly would take time and practice to master it. While I’m currently in the process of tanning the hide of one of our Soay Sheep, leaving the wool intact on the hide means that I’m taking a much more simplified approach.

I’d love the opportunity to try out a more traditional tanning method and may embark on the journey to do so.

Who owned the tannery?

Truth be told, I’m not really sure who owned the tannery throughout it’s time.

On October 8, 1757, Joshua Bodley, Thomas Barker, George Brownrigg, Charles Blount, Joseph Hewes, and William Jackson formed a corporation to operate a tan yard (Chowan County Record of Deeds K-l:93).

Over time, things changed between the corporation and in 1782, the tan yard was mentioned in the will of one Samual Black (there are no deeds that show when the acquisition was made). The property was divided between his heirs, Elizabeth Young and Dorothy Roberts.

It changed hands a few times in the decades following that, and the plots continued to be divided into different ways, shrinking into smaller and smaller parcels.

One thing that I did want to point out though, is the will of one Josiah Collins (Proved 16 April 1819), who stated, “I give and devise and bequeath to my grand-daughter Elizabeth Littlejohn my tan yard adjoining the town of Edenton beginning at the Northwest Corner of the Bark House and running thence Eastwardly till it reaches the North East corner of the Bark House thence southwardly until it intersects a line drawn Westwardly from the Saw Pit, so as to include all the houses appertaining to the tannery together with all the improvements utencils and stock of leather whether tanned or untanned, hides bark and everything appertaining to the said Tannery excepting only thereout the spring which is to be for the common use of the Rope-Walk and the Tannery.”

Josiah Collins was a very influential figure within the history of Edenton, so though it stands to reason that this was the same tannery as we mentioned previously – it seems to be a different tannery. I plan to dig a little deeper into the Collins family another time, so I’ll share more about that tannery and *hopefully* it’s location.

In an effort to keep this post from growing too lengthy, we shall end it here, but I hope that you learned a little bit more about the town of Edenton.

If you have any knowledge of the Edenton Tannery, or any pictures from the excavation, please reach out to me!

For a deeper dive into tanning, I suggest reading “The Early Vegetable Tanning Industry in Georgia: Archeological Testing at the Clinton Tannery” by Daphne L. Owens and Daniel E. Battle or even “Archeological Investigations of the Edenton Snuff and Tabacco Manufacture” by Robert W. Foss, et. al.